Friday essay: ‘An oasis in the desert’ – Jackie Huggins reflects on her deep history with Carnarvorn Gorge

- Written by The Conversation

Ngya Bidjara/Birri Gubba Juru marra. My name is Jackie Huggins. I am the mother of John. I am also the daughter of Rita, and Albert and Rose are my grandparents on my mother’s side. My father is Jack Huggins. My grandparents are John Henry Huggins the third, and Fanny: all people from Queensland in Australia.

My father was a free man. He wasn’t under the Aboriginal protection legislation of the state of Queensland, or of the country, in fact. The Aboriginals Protection Act – or Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 – restricted many Aboriginal people in Queensland to remaining wards of the state, controlling their employment and other aspects of their lives.

To be outside this Act meant less restrictions on where you could go, who you could marry, and so on. Your life was not controlled.

However, my mother, under the auspices of this Act, was rounded up in the 1920s and put on the back of a cattle truck, removed from the beautiful Country of ours, from Carnarvon Gorge in Central Queensland, and taken over 600 kilometres east to Cherbourg Aboriginal Mission along with five of her siblings. She had 13 siblings in total.

My mum led the life of most Queensland Aboriginal women under the Act in the 1920s. They went into domestic service at the age of 11 or 12, sent to slave out on cattle station properties all throughout the state. My father did not have to do that. Instead, he served in the Second World War and was a prisoner of war on the Burma–Thailand Railway. While he did come home and fathered three healthy children, he died at the age of 38.

I don’t know much about my father’s Country, Ayr, North Queensland – Birri Gubba Juru – where he and his children were born, but I certainly know a lot about my mother’s. It is also the Country of my uncle, Fred Conway, who has been my cultural and spiritual advisor over many decades.

He was a ranger out at Carnarvon Gorge for 30 years and still takes school excursions there to show, share and teach the Deep History of our Country. He knows every inch of that Country – the Gorge – including the wildlife, plants, birds, where the women’s sites are, and the men’s sites. He has a talent for impressing upon every visitor how unique that Country is to us, how special and sacred the Country is for most Bidjara people.

We share that place with a number of other groups. Carnarvon Gorge is on part of the Country of the Gayiri, Nguri, Garaynbal (Karingbal), Gungabula, Yiman and Wadja peoples. In 2020, we had a meeting of the Gathering of the Clans, and we hope that, through Treaty rights that are ensuing in our Country, Treaty might become a way for us to get much more out of that than Native Title, as Native Title has not served us so well, so Treaty could assist more in terms of access to legislation.

The Mabo Judgement (1992) of the High Court of Australia recognised that native title existed and that the notion of terra nullius was a fiction. The Australian government introduced the Native Title Act of 1993 to allow a process for recognising Indigenous title to land. However, this is a flawed process in many ways, and it generally relies upon non-Indigenous documentation to prove title.

Anyway, we lost that because the claimant area was far too great. But Carnarvon Gorge area is clearly Bidjara Country. The people who have claim to that – the Karingbal people – will also acknowledge our connection to that Country. The government determined that they were the last people standing under the Native Title rules of the Commonwealth, declaring the Karingbal own this Country. But the Karingbal people say, “We know that you own Carnarvon Gorge, and you are the spiritual owners of that place”.

Honest conversations about colonialism

Every year I go back there, to Carnarvon Gorge. I try to make it twice a year sometimes. And in fact, as I write this, I have just returned. When I visit, I do as my mother Rita did when she visited there. She would walk around, she would feel the earth, and she would kiss the ground upon which she knew our people had been for tens and tens of thousands of years.

My mum was a single mum. She was very influential in my life. She grew up four kids without my father, who had passed so young, and she too had a yearning for her Country. As you get older, particularly for our mob, you want to go back to those places. You just yearn for that Country that you came from, even though she was rounded up on the back of a cattle truck and sent to Cherbourg – some three hours north-west of Brisbane – at a very young age. Where she ended up was my mother’s adopted home.

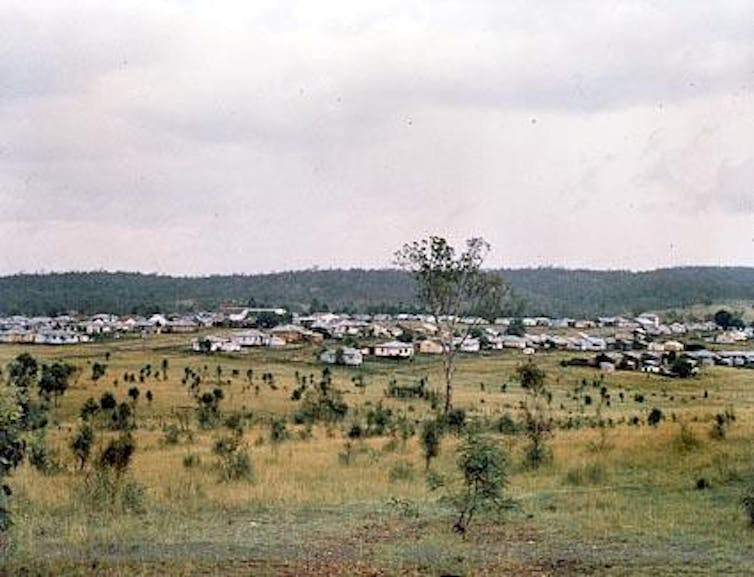

Cherbourg was a mission reserve where our people were put, forcibly removed from their Countries. We had a big inquiry about children being forcibly removed from their families. This was known as the Stolen Generations Inquiry and it was hoped that stolen children could be reunited with their families and communities. Native Title was supposed to fix that too.

But unfortunately, it has created all kinds of deep divisions within our communities as well. It is very restrictive as people have to prove they were always on their land and Country to gain native title rights. Of course, this is often impossible for those who were removed from land.

We are relying now on our Treaty that I’ve been working on, on and off, for the past four years in Queensland. Treaty is an agreement between two parties, and if Native Title is lost then it is lost forever, despite appeal processes. Treaty therefore offers an opportunity for traditional owner groups to negotiate agreements with governments and other stakeholders outside of Native Title.

Treaty would acknowledge that sovereignty was always and will always be intact. But unfortunately, due to the Voice Referendum held in 2023, the opposition party in my state of Queensland said they would not entertain a Treaty if they come into power at the next election. In October 2024, they were elected into power.

Hopefully that won’t stop us, because two budgets ago the Queensland government committed funding to pursue Treaty and Truth-Telling, quarantined against COVID and quarantined against natural disasters. Actually, we think this failure of the majority of the Australian people to support the Voice is one of those natural disasters.

Regardless, our Treaty will continue in some shape or form, aided by Truth-Telling. Truth-Telling has to be an honest conversation about what has happened through colonisation and its continued effects on the Indigenous population. It will enable all people to share their truth, officially document their stories, and uncover the untold and unrecognised history of this country.

In the state of Victoria, they have a Treaty process and a Truth-Telling Commission that is happening now. Victoria is about five years ahead of Queensland in this regard. Queensland only began their process in September 2024.

A deep affection for history

Back to my Country, Carnarvon Gorge. This very special and beautiful place called Carnarvon Gorge is in the centre of Queensland. It is an oasis in the desert. It is very remote, but for many decades now, my uncle has been doing the talking up of that Country and educating people – educating whoever wants to listen – about the beauty and the magnificence of that Country.

So when historian Ann McGrath came to me and said, “We’re concentrating on six sites through Marking Country [the new website], we would love to do one for Carnarvon Gorge”, I put my hand up, and so did Uncle Fred.

This digital project aimed to present Deep History on Country in the ways that Indigenous custodians wanted to present it to a wider audience. Uncle Fred and I came to a conference at the Australian National University in Canberra and spoke about the work that we’re doing.

Ann visited Carnarvon Gorge with another researcher, Amy Way, and we sat there and took photos and videos of the beautiful Country that is Carnarvon Gorge, including the rock art of my Country. It has many sites that are available to the wider public to have a look at, but there are many sites that Uncle Fred has taken me and my family into that he won’t show to white people or any other visitors. I feel very special about that.

For me to have come back to thinking about academic history and reflecting on what “history” means for me as an Aboriginal woman is a bit of a different turn. To explain, as well as publishing histories of my family and many articles, I have done over 45 years in Aboriginal politics in our country, across all kinds of areas: reconciliation, domestic family violence, prison reform, Stolen Generations, you name it.

I’ve been on every board – except a skateboard, and you wouldn’t want to see me on that! But that’s the extent of my career. And of course, I am an Aboriginal woman historian as well.

I have a deep affection for history. I saw the way that my mother was treated as an Aboriginal single mum, and I saw the way that history wasn’t even taught in our schools. And one day I said, “I want to be a historian, I want to write, I want to teach, and I want to talk about history”, and that I did. It was a nice dream come true.